“Fail gloriously, students. Wood grows on trees.”

— R.E. Malphus

Obituary: Dr. Reginald (R.E.) Malphus, 1922–1999

Inventor of Things, Beloved Wood Shop Teacher, Keeper of Sawdust and Secrets.

WESTON, VT — Dr. Reginald E. Malphus, 77, passed quietly in his workshop on a Tuesday afternoon, surrounded by the walnut and brass contraptions that defined his peculiar genius. Known across Windham County as “The Professor”, and despite having no formal education beyond a mail-order certificate in “Advanced Pedagogical Mechanics,” he spent 35 years teaching wood shop at Weston Union High School, where he became a fixture in flannel, spectacles, and a perpetual film of sawdust.

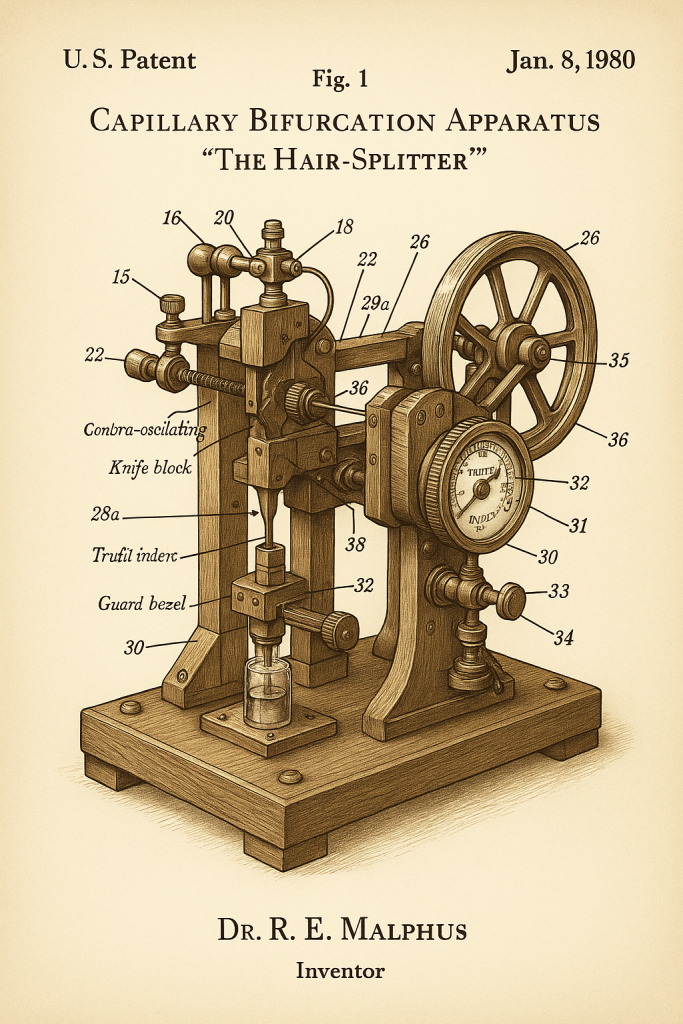

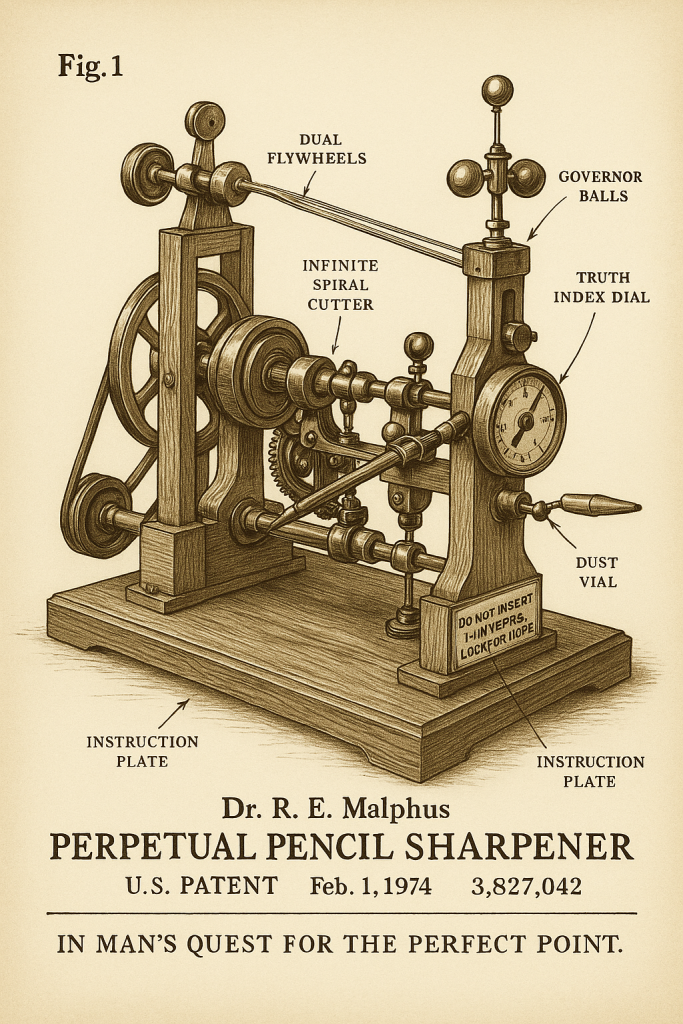

His later life was consumed by his workshop and the endless pursuit of what he called “useless necessity.” Machines like the Capillary Bifurcation Apparatus (known colloquially as The Hair-Splitter), The Perpetual Pencil Sharpener, and the Red Herring Detector never produced practical results, but they produced laughter, wonder, and some mild burns and abrasions. He called his legacy “proof that usefulness is overrated.”

He is survived by his wife, Ethel (who patiently tolerated the endless grind of belt drives and whir of governor balls), two children who inherited his clumsiness if not his curiosity, and dozens of former students who claimed to have learned more in Dr. Malphus’ wood shop class than in the 10 years that preceded.

───── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ─────

At the front of the room, chalk dust on his sleeve and glasses slipping down his nose, stood Mr. Malphus, cardigan famously worn under his shop apron, tie tucked in for safety.

“Class,” he would say, voice low and steady, “Remember — perfection is not to be achieved.”

A long pause as his eyes circled the room.

“It is to be traversed, endlessly, and viewed from every angle with no real expectation.” “Life, then, is nothing but a controlled sprint ending in a crisp, clean cut .” As he zipped through a scrap piece of two by four on his band saw.

His students adored him, though most never followed through on their assignments. Malphus believed shop class wasn’t about projects anyway, but about process.

One semester he spent four weeks having the class design elaborate clamps the sole purpose of which was to hold other clamps tightly together. After three weeks a student protested and his answer “but they have nothing else to hold onto.” After the fourth week, the experiment ended. They spent the whole fifth week analyzing why they did what they did, the past four weeks.

Another time he had his class build small wooden boxes that could not be opened once assembled, insisting:

“Are you certain there is nothing inside?”

Behind the perpetually furrowed brow was a kind, patient man. Quick to laugh when a jig failed, quicker still to admire a clever mistake. He didn’t grade on completion — he graded on unconventional progress.

Malphus compensated participation with his direct attention, focusing on each class, one individual at a time. His classes were always full and participation was exceptional and consistently high. There were a couple of occasions where parents would talk about his irreverent and unconventional methods, but the school board felt, early on, that it would be safest tucking him away teaching an elective course, so wood shop it was.

For the one’s who caught on, the students always got their money’s worth. There was always a point to be made, and in his own fashion, Malphus circled around it, never pointing directly at it. But he would make sure the class knew the methodology and let each student engage their own reasoning.

Every session, a different experiment, and in every class, he saw an opportunity to excite his students to the prospect of “an experiment gone sideways”. Mr. Malphus seemed to be prepared for every contingency.

He often tinkered after the bell, way into the evening. His wife, Ethel, always packed some extra snacks for him, knowing that he may stay late. The corner of the classroom was always piled with gears, brass rods, and wooden frames. Students whispered about the “secret machines” that he worked on at home. He just waved it off.

“Just try it, guys.” he could be seen saying when he finally lifted his head from his work, stuffing his ham sandwich in his mouth as if he was already missing something..

“There is value in every experiment.”

───── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ─────

A color slide from 1979 shows Mr. Malphus setting up for the Weston Union Fall Fair.

Reginald Malphus carted the Capillary Bifurcation Apparatus to a makeshift booth under a striped canvas tent. Brass gleamed golden in the October sun. He produced some type of polish and he proceeded to put a final shine on the metal parts, then, methodically polished the wooden components.

He then set up a small hand-painted sign on poster board that reads: “Hair Splitting Demonstrations — 25¢.” By 9 am, children began to cluster around, quarters laid on the table, laughing as he solemnly threaded a hair into the collet.

He begins to explain the process in his teacher’s cadence, tapping the truth index meter with his pencil stub. The resulting split filaments drop uselessly into a glass vial — and the kids cheer as though they’ve witnessed a miracle.

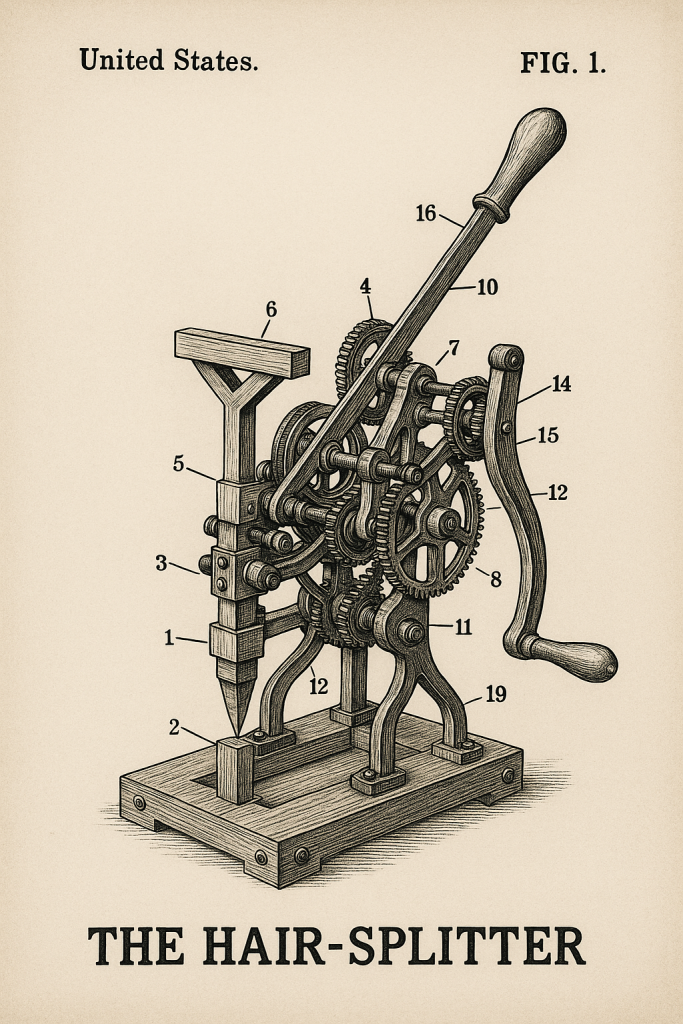

“Now listen closely, people. You may think this is just a jumble of brass and oak, but what we have here is the Capillary Bifurcation Apparatus — or what I like to call The Hair-Splitter.“

“See this collet? That’s where we feed in a single human hair. Just one. Doesn’t matter whose — your own, your neighbor’s, or one you’ve found on the floor”, Malphus professed with the bravado of a stage actor.

“The machine doesn’t discriminate. Now, this micro-meter micrometer here advances the hair, exactly one one-hundredth of a millimeter at a time, into this contra-oscillating knife block. That means the blades snap back and forth like two arguing lawyers, until at last the hair is neatly divided into two smaller, utterly useless hairs.”

“Now, note the Truth Index Meter. You’ll see the pointer hovering mysteriously between Zero and Eleven. The numbers don’t mean anything for the purpose of this particular demonstration, but they give the impression that they do, which is half the point of science. The other half is actually discovering something useful. We won’t bother with that”.

“Regardless”.. his voice lifted and then paused to be sure all are still paying full attention.

“Once the split is achieved, the curled fragments tumble down this little chute into the Result Vial. And when that happens, children, you may cheer! you may jump and shout! — not because the world has changed, but because you’ve witnessed the improbable reduced to the irrelevant.“

“And remember this: when one hair becomes two, the lawyers are no longer arguing. But it is you, you are advancing science. And advancing science, even useless science, is worth exactly 25 cents at the county fair.”

To their amazement, Mr. Malphus revealed a hidden quarter from the ear of each child as they left his demonstration tent. He delighted in seeing their faces as he returned the coin to each one of them. “also… remember”, he said, as if he had concluded this demonstration a hundred times before, and with perfect timing:

“Science is just magic that insists on showing its work.”

───── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ─────

Below, the original patent plate for Dr. R. Malphus’ Capillary Bifurcation Apparatus, or “The Hair Splitting Machine” [view his patent here].

A later design for an automated “Capillary Bifurcation Apparatus“

───── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ─────

“Normally.. once the point is made, the conversation ends, right? In one’s mind there is one clear winner and one clear loser. Ok!

The problem, then, is just that not all parties agreed on who that person is.” “Or even, why it really matters when winning is a distraction, anyway.””Winning, is never a point to be made.”

“Maybe besides the point.”

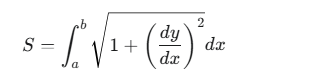

“This machine proves that the point is not perfect, the line (of reasoning) doesn’t end just because you walk away thinking you have made the better point. The point actually goes on forever, following a line of reasoning from negative infinity (−∞) to positive infinity (+∞).

“Or from the point of view of the line:

“Conclusion: Most opinions could never withstand the rigors of science, but that is exactly where they need to be – held up to the light, with utmost scrutiny!”

“Keep questioning, people. Without expectation. Everything.” “Question everything.”

───── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ─────

Captured in 1987, two of his former students stop by to see the operation of his newest machine. Malphus cranks a leather-belted pulley on his “Red Herring Detector”, and the fish-shaped dial swings madly back and forth indicating the detection of a new diversion designed to distract from the real issues at hand.

His wife Ethel peeks in from the kitchen door, unimpressed. The camera flash catches her expression — part fondness, part exasperation — while Malphus beams with childlike pride, oblivious to her rolled eyes.

───── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ─────

In 1993, Dr. Malphus was given an honorary doctorate by the University of Vermont for his devotion to science, to his students, and to his living testimony that the proof is in the pudding, (though he did not live to see his design for the “Pudding Prover”, he did design and develop a prototype “Light Of Day Machine”, among others.

───── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ─────

More prototype inventions from the workshop of Dr R.E. Malphus, Inventor.

The Fenskein Automatic Tissue Dispenser

The Auto-Crank Marshmallow Machine

The “Clip-o-matic” Paper Clip Straightening Machine

The family invites all to a brief service and memorial at Cucanelli’s Funeral Home and Quality Used Motors, this Saturday at 5:00 pm.

───── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ─────